…but fact-checking and awareness may not be the most effective strategies to defeat social homophily from so-called “filter bubbles.”

“Your Echo Chamber is Destroying Democracy.” “The Filter Bubble Explains Why Trump Won and You Didn’t See It Coming (The Cut).” “Journalists and Trump Voters Live in Parallel Universes.” These are just three choice examples of news publications that have factored filter bubbles as an agent in the destruction of democracy in the age of Trump and why Trump’s election caught many off guard. Filter bubbles, so the common wisdom goes, contribute to the kind of social homophily that stalls democratic debate, eases the rise of fascism, and leads readers to trust media sources based on partisan or ideological identification rather than epistemological rigor.

The concerns regarding the democracy corroding-agency (or agencement) of filter bubbles predates the post-2016, U.S. political exigency of the topic. Although the term and its derivatives has come to refer to both algorithmically-driven and human processes of cognition (I will come back to this later), the original term is credited to Eli Pariser, who coined it in 2011 to describe increased user personalization in indexing algorithms on search engines and content curation on social media interfaces have come to insulate individuals into an ideological “echo chamber” in which we are isolated from other points of view. Drawing from Putnam’s concepts of “‘bonding’ capital’ (in-group social capital) versus ‘bridging capital’ (capital that gathers the stakeholders of an issue across in-groups), Pariser argues that predictive modeling in search engine algorithms encourage ‘bonding capital,’ but limit the internet’s potential of ‘bridging capital’ by limiting what information we encounter and who we hear, often in accordance to profitability in an ad-revenue driven market. Furthermore, he argues, the personalization of algorithms fundamentally “alters the way we encounter ideas and information (9)” in ways that include testing our attention spans towards uncomfortable points of view, thus engaging in a complex process of (in my words, drawing from Hayles) technogenesis.

For these reasons, there is a potential to create algorithmic “parallel universes” in which audiences cannot agree on the shared facts necessarily to have productive political dialogue. Therefore, drawing from influential political theorist John Dewey, Pariser declares that the “filter bubble” is danger to democracy. Over the next few weeks, I’m going to try something a little different with this blog and do a short series challenging the common wisdom around filter bubbles. Are filter bubbles actually the danger made out to be? What role do attempts to fight their activities via digital literacy initiatives and “bubble busting” technological innovations (“Coders Think They Can Burst Your Filter Bubble With Tech” (WIRED),“Technologists are trying to fix the filter bubble problem they helped create (MIT Technology Review) actually play in response? Given that digital literacy initiatives tend to backfire, it’s worth challenging our presumptions about the role these procedures play in democratic discourse, and, by extension presumptions we have about democracy, public space, and the evaluation of knowledge.

Over the next few weeks, I’m going to try something a little different with this blog and do a short series challenging the common wisdom around filter bubbles. Are filter bubbles actually the danger made out to be? What role do attempts to fight their activities via digital literacy initiatives and “bubble busting” technological innovations (“Coders Think They Can Burst Your Filter Bubble With Tech” (WIRED),“Technologists are trying to fix the filter bubble problem they helped create (MIT Technology Review) actually play in response? Given that digital literacy initiatives tend to backfire, it’s worth challenging our presumptions about the role these procedures play in democratic discourse, and, by extension presumptions we have about democracy, public space, and the evaluation of knowledge.

Initially meant to be one blog post, I went full blown post-LOTR mid to late-2000s fantasy franchise on you and made this series a trilogy. With this in mind, let’s start with some good expository, monologue-y world building establishing the quest by word of wizard:

What the fuck is a “filter bubble?”

What is A Filter Bubble?

The term “filter bubble” has developed enough myriad, heteroglossic uses and connotations to fill a dissertation chapter. (Hopefully. Idk maybe I’ll chat with my committee and get back to y’all on that). Pariser’s is good enough for this installment of my short series. To refresh: filter bubble is his term for increased user personalization in indexing algorithms on search engines and content curation on social media interfaces have come to insulate individuals into an ideological “echo chamber” in which we are isolated from other points of view.

Search engine indexing algorithms: To index points of reference is to organize these references according to reference value. Indexing algorithms arrange references like Facebook friends’ statuses or search engine results in according to the “value” — i.e., relevance — of an inquiry or the value and relevance of a friend’s status. For example, on Tuesday morning, September 11, 2001, many Google users searched for “Twin Towers” to get news updates only to get results like “World Trade Center Boston” or WTCA (“The Evolution of Search“). This is because Google’s indexing algorithm at the time assigned “value” on the basis of overall popularity. Now, trending (exponential popularity growth in a short amount of time) factors into calculated “value.”

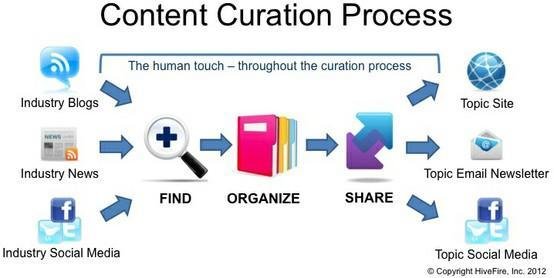

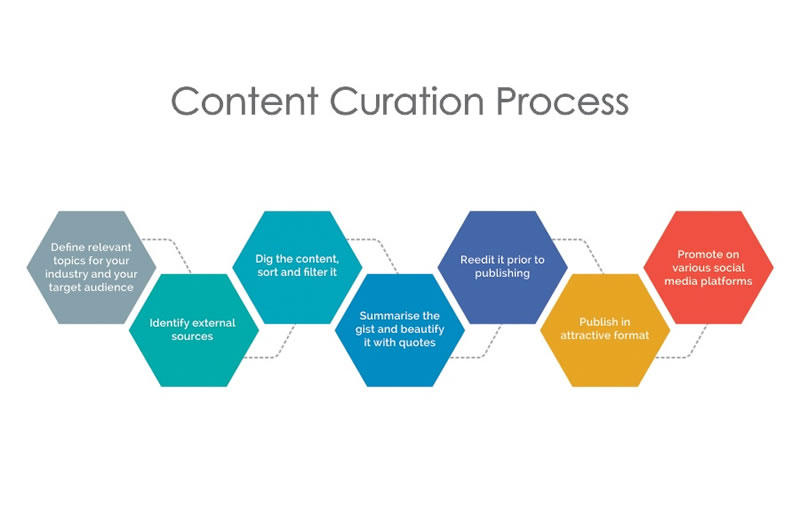

Content Curation: Beth Kanter — whose blog was deemed the most relevant to my search by Google indexing algorithms when I googled “definition of content curation” (because the best I could come up with was “like curating a museum, but like, if you wanted to stagger the time that different viewers experienced the museum artifacts and also could also disseminate the aura of the Mona Lisa across space) — defines content curation as

“the process of sorting through the vast amounts of content on the web and presenting it in a meaningful and organized way around a specific theme. The work involves sifting, sorting, arranging, and publishing information (Kanter “Content Curation Primer“).

“Content curator” can be a job title for a person. Hell, we all practice some form content curation on our social media feeds, especially if you are aiming to recruit enough followers on Tumblr or YouTube to make a Patreon account. Almost all content curators who make visible or obscure the index references — again, think of search engine results and FB friend statuses as examples in this context — are algorithmic. I think we went over pretty well last time while algorithms are not becoming museum curators any time soon (hopefully) and make equally abysmal censorship arbiters.

Personalization: Integrating the individual user’s movement through on and offline space into relevant factors in the calculation of “relevance” or “value.” To go back to the 9/11 example, “popularity over all time” and “currently breaking news” factor into adjusting the indexed results according to calculated value. Personalization brings in individual factors. For example:

- browser history

- purchase history

- demographic background

- IP address

- websites you are most likely to log into at what place and what time

- how often you use your phone vs your computer to browse the web (and what webpages in particular).

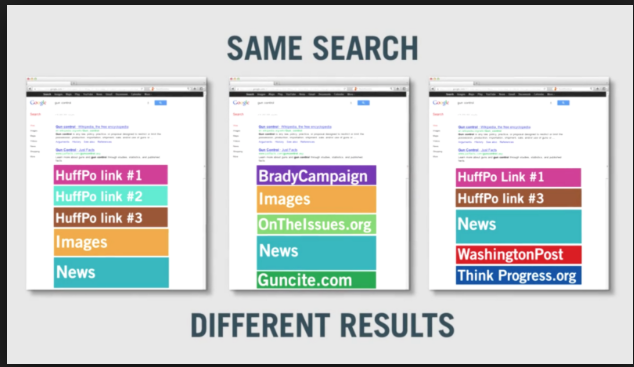

A simple platform might not be able to do so effectively without third-person party data sharing, which is why this data is such a hot commodity to advertisers. In the case of FB, predictive calculations include factors like the Facebook pages liked by your friends or how long your cursor hovers over a status or ad (even if you do not click it or interact). The most simple and obvious example of personalization in search engine algorithms is how two people in the same coffee shop can google the same thing at the exact same time and get different results.

Thus, algorithmic indexing is a form of content curation in that it calculates “relevance” based on personalized histories in order to curate what content appears on your screen. Or, more accurately, instead of centering the human user as the “center” of the experience, and see algorithms as “walling off” or “bringing” information to you, think of the role of algorithmic organization in algorithmic ecosystems a content curator for a platform or multiple online infrastructure (not a typo). Your digital self as composed up of all the digital dividuations of “you.” You are part of the content that is filtered or valued to different audiences and also made up of/through what information reaches you and how you come to establish “meaning” “relevance” and “value.”

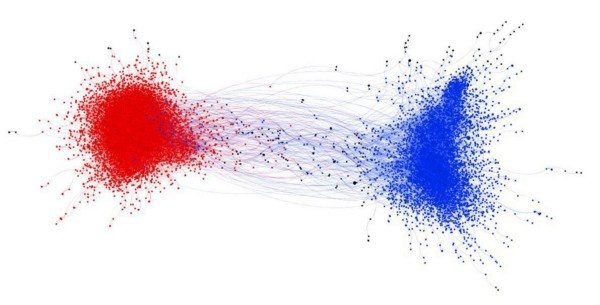

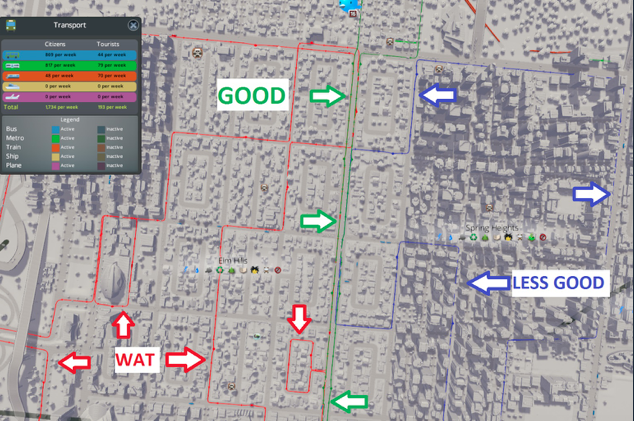

To sum up, algorithmic practices of search index engines and other content curation are not insulated islands, but are better understood as online traffic direction; not filter “content” or “voices” that reach a single stable individual. In this context, instead of thinking a filter bubble like this:

We can think of it more like this:

The role of the human “I” within the filter bubble is not so much

but more:

Given our embeddedness within algorithmically-mediated environments, the model of understanding lack of engagement with information as due to insulation or lack of “exposure” needs to be re-evaluated to understand a more dynamic model of information activity than the notion of a static, stale “bubble” often implies for reasons I am about to provide.

Visualizing the Echo

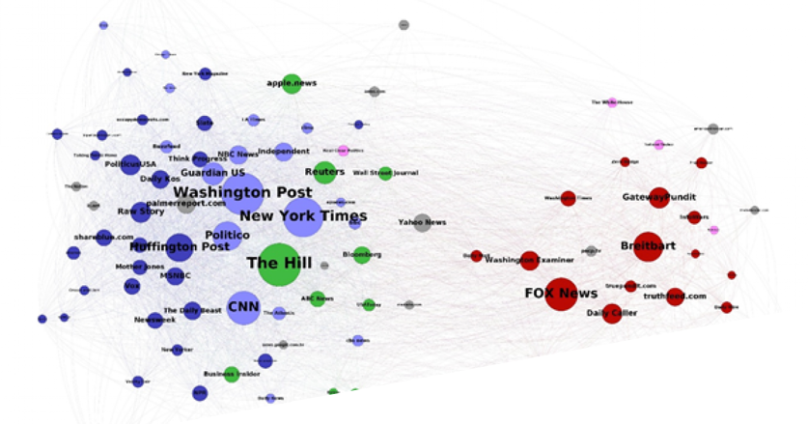

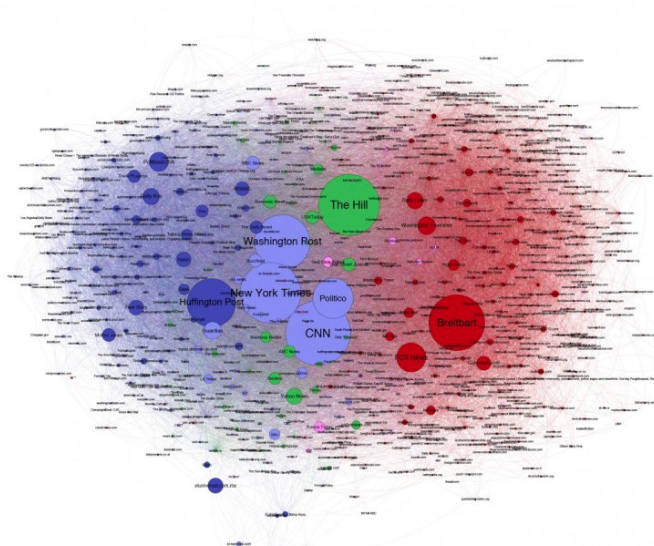

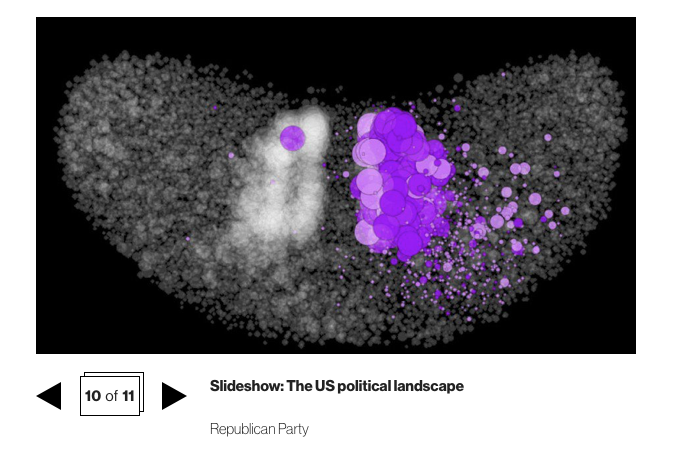

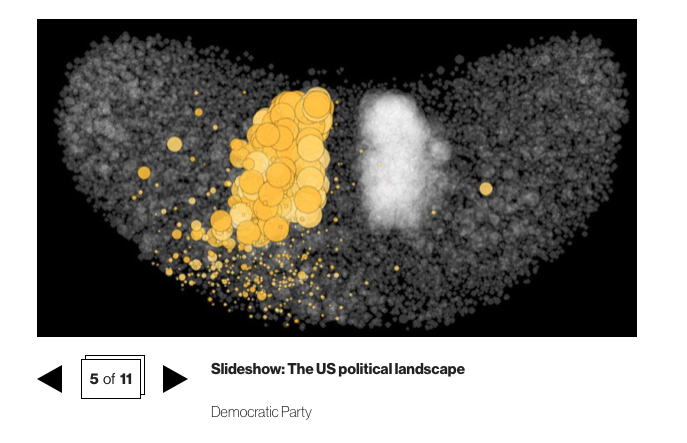

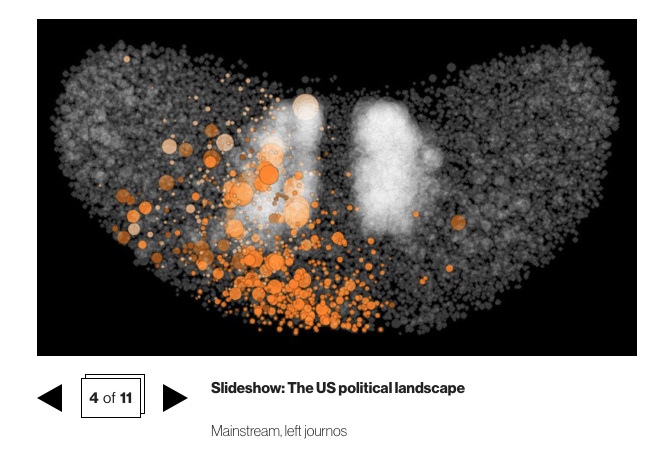

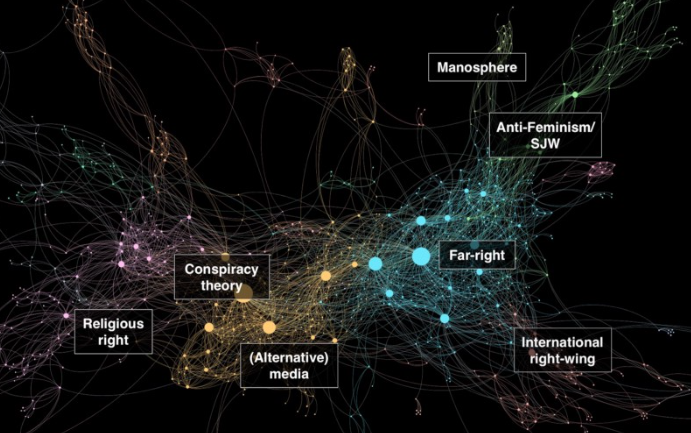

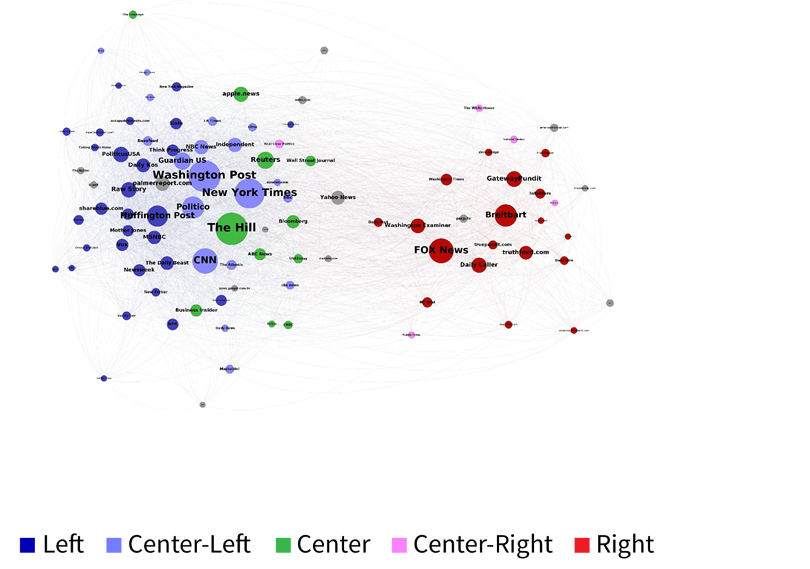

I used those visual metaphors to figuratively represent how to re-shape the notion of “the bubble” outside of the static connotation that the “filter bubble” metaphor can imply. But what’s a better visualization of how they work in the context of political discourse, news consumption, and interaction? The graph below is taken from a 2018 study conducted by Harvard’s Berkman-Klein Center ((Benkler et al, 2018) on how media and information quality is judged in an era of algorithmic curation, bots, “fake news,” etc. It shows networks of engagements across media sources (see Methodology in article linked above).

The first thing we can see upon closer examination is that although these network media ecologies are divided into two main clusters, we can see the near-translucent paths of interaction that can be traced between each node, including the ones too small to represent to scale in this visualization. There is a sharp ideological divide, but the ideological divide is more like set of “clusters” instead of separate spheres in which there are tighter connections between different sources (represented by nodes in this network visualization). But the ecology “as a whole” is still connected, possibly due to meta commentary and re-purposing information.

The first thing we can see upon closer examination is that although these network media ecologies are divided into two main clusters, we can see the near-translucent paths of interaction that can be traced between each node, including the ones too small to represent to scale in this visualization. There is a sharp ideological divide, but the ideological divide is more like set of “clusters” instead of separate spheres in which there are tighter connections between different sources (represented by nodes in this network visualization). But the ecology “as a whole” is still connected, possibly due to meta commentary and re-purposing information.

The next thing we can see is that the divide is not between Democrats and Republicans “The divide is between the right and the rest of the political media spectrum (Benkler et. al, “Understanding Media”).” Sure, the The New York Times or Huffington Post or any paper can have conservative points of view or editorial frameworks. It just means that the notion of an environment in which we “are exposed only to opinions and information that confirm to our existing beliefs” is too flattening and does not account for how information traffic actually flows, and how different ideological positions are “bubbled” different in ways that are political but not even necessarily strictly partisan. So, overall, instead of thinking of filter bubbles in our media ecology like this:

A more comprehensive understanding of the wider online environment looks more like this:

(higher resolution here).

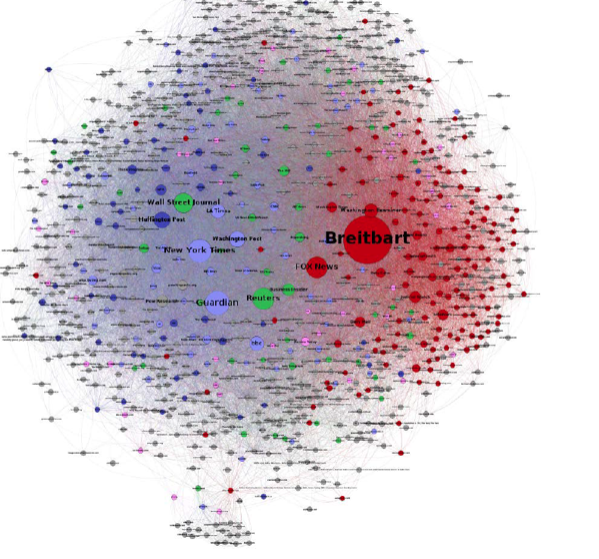

If you wanted to focus specifically on a topic and platform, for example, how immigration was discussed on Twitter in 2016, that niche would look something like this:

Another example I found is this 3-D visualization of the network of news source relations(see link below) from MIT:

(see full slideshow for other spheres, like local news, party politics, different movements and mainstream and non-mainstream sources, etc.). Polarization exists, sure, but there are still layers of interaction and overlap in which one individual can participate in multiple publics.

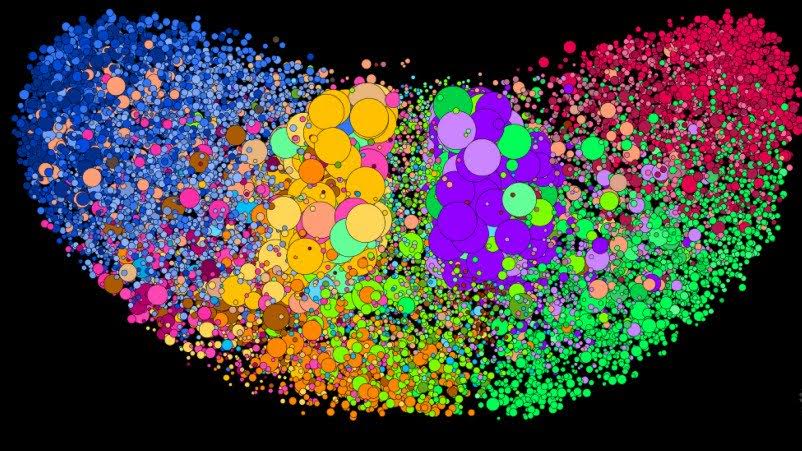

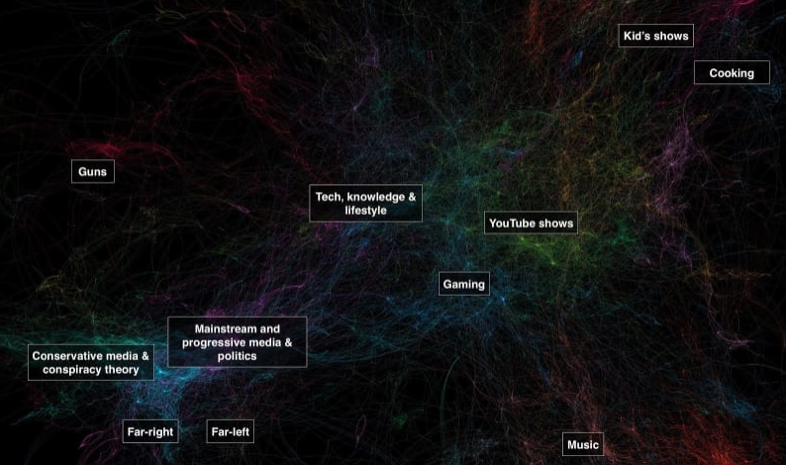

So not all filter bubbles are “created equal” in that some networks are more internally cohesive than others (conservative ones). On a related note, not all algorithmically generated filter bubbles exercise the same power over the user for reasons that cannot be reduced to advertisements. For example, let’s look at Kaiser and Rauchfleisch’s Medium dispatch on their project on the role YouTube suggestion algorithms play in radicalizing the far right. (“Unite the Right? How YouTube’s Recommendation Algorithm Connects the Far Right”). Again, see post for methodology. The image below shows “YouTube channel network with labelled communities (node size = indegree / amount of recommendations within network; community identification with Louvaine)”(see source linked above).

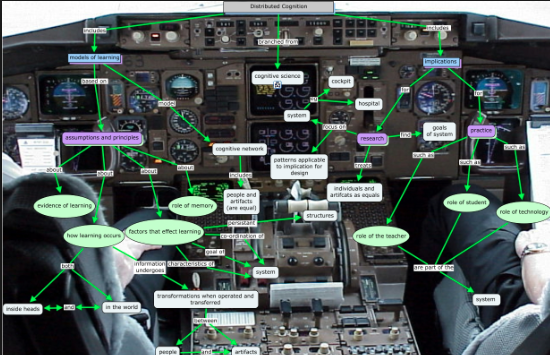

. This distance-vantage maps out connectivity in YouTube by way of topic and genre. Political channels are the Florida of YouTube, more densely populated than the much larger, less concentrated neighborhood of “Gaming,” for example, and its occupants are closer isolated with each other and not directly connected to other realities, like Kid’s Shows or even Guns. If we look at this map again focusing on how many search algorithm traffic congregates around specific uses, we see:

The authors go into more detail than this visualization provides to note that while both The Far Right and The Far Left channels are much more likely to be suggested than repostings from Fox or CNN (possibly due to copyright infringement or that YouTube is better for content not hosted elsewhere), mainstream media channels engage each other. The Far Left as dominated by The Young Turks is often recced back to mainstream news outlets but the path of suggestion is not mutual: the Far Left is somewhat isolated. I speculate based on the writers acknowledgement that Left YouTube consists of “communist, socialist or anarchist channels” means online cross-community engagement is less likely between different ideological positions. On the other hand, The Alex Jones Channel is mutually connected to Fox, other another weird-ass challenges-your-motivation-to-ward-off-the-extinction of our species channels I’m not name dropping to not give them the search engine hits, and GOP official accounts. This means that while watching CNN’s Channel won’t lead the recommendation algorithm to predict that you might like the Young Turks, the predictive model may calculate that if you watch CNN than you might be interested in Fox and MSNBC, and if you watch Fox, it will likely suggest Alex Jones. The point is that this topical algorithmic sorting is not meant to be partisan. CNN, Fox, and MSNBC are all lumped under “mainstream news” as this is both a topic and a genre. But it ends up forming an ideological online niche because of network engagement that reflects the media ecology as a whole.

Once you are “in” the right-wingo sphere, it can be difficult to get out if you are following recommendation algorithms snowball-style like the researchers do in this study and like a bored 15 year old does on a 2:00am school night. Right YouTube is intensely self-connected and broken down into tightly intersected clusters.

To go back to politics and news YouTube as the “Florida of YouTube,” clicking videos in this topical peninsula will not necessarily lead you back to YouTube cooking shows, unless you happen to like politics, news, and cooking shows independently. Similarly, Far Right YouTube will not “lead you back” to un or less connected networks. “You watched this video on How Feminazis are Hypocritical Cunts for Appropriating the Word “Nazis,” you might want to watch this video by “Yolanda Makes Cakes” — said no hypothetical anthropomorphized algorithm rationale ever. However the farther you get in self-referential right YouTube, it’s hard to wander back from the fascist Florida keys, because you are less likely to have mainstream news sources suggested outside of Fox. This is the place where right wings are radicalized on YouTube.

As I wrote last week, algorithms are moralizing and normalizing frameworks and interpreters. Algorithmically controlled movement flow also ascribes value to certain movements and subjects over others, including stigmatizing some movements over others (go back to the definition of “personalization” and consider the difference between a Kroger card and a EBT card (Eubanks)). However, what these examples show is that the notion that we are not exposed to other beliefs in “a filter bubble” is incorrect. Movement facilitation by algorithms can still lead to ideological enclaves within dynamic relationships, but “movement” sprawls across plateaus. The actual enclaves, or space that emerges within discourse, enact a certain persuasion when their overt politicalization becomes ambient. Personalization algorithms can elevate some “movements” over others by calculating relevance to an individual user that through personalization programming. The human is not insulated. It is that where we “go” online, what comes to meet us there or even structure this environment, what we discuss in what spaces (and how), with whom, is movement tracked by and co-directed by algorithmic computation. In ways with normative and political consequence

What Does This Mean Going Forward?

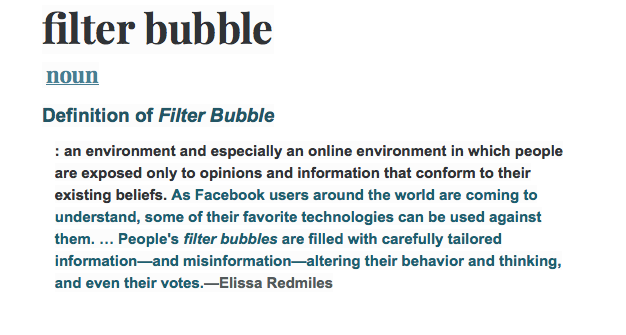

The definition of “filter bubble” that entered the Merriam-Webster dictionary (2018) is:

In this definition, the word “exposed” implies an environment in which oppositional views are never encountered. As we saw above, this is technically not true in the strictest sense. In fact, the Benkler et. al article above concluded we encounter more views online than we would offline. That said political polarization is very much a threat to democratic dialogue when a “parallel universe” of facts does exist.

In this definition, the word “exposed” implies an environment in which oppositional views are never encountered. As we saw above, this is technically not true in the strictest sense. In fact, the Benkler et. al article above concluded we encounter more views online than we would offline. That said political polarization is very much a threat to democratic dialogue when a “parallel universe” of facts does exist.

However, if the problem is lack of “exposure” to other ideological perspectives, or surely this could be fought through fact-checking methods, digital literacy such as curriculum suggested in California public schools, and using digital tools? Tech industry professionals and online platforms have developed ads like Unfiltered.news, Discors, and Echo Chamber Club that seek to purposefully introduce and cultivate opposing viewpoints in one’s news consumption, projects like Buzzfeed’s “Outside Your Bubble” project “an attempt to give our audience a glimpse at what’s happening outside their own social media spaces,” or FlipFeed, which offers the experience of “browsing someone else’s Twitter” by curating randomized* content, or apps like PolitEcho, which attempts to detect bias in your Facebook consumption based on the “Liked” pages of your friends.

Of course, humans would have to invested in learning how to do this, and companies like Google and Facebook would be required to be more transparent about how online indexing algorithms structure digital infrastructure, often below the awareness of many users. But, in theory at least, a combination of technologies and educational practices would eliminate these filter bubbles?

Nope.

In the same 2018 Berkman Klein with which I began this entry, the researchers concluded that:

“the claim that online, we encounter only views similar to our own…isn’t completely true. While algorithms will often feed people some of what they already want to hear, research shows that we probably encounter a wider variety of opinions online than we do offline, or than we did before the advent of digital tools. Rather, the problem is that when we encounter opposing views in the age and context of social media…we bond with our team by yelling at the fans of the other one. In sociology terms, we strengthen our feeling of “in-group” belonging by increasing our distance from and tension with the “out-group”—us versus them. Our cognitive universe isn’t an echo chamber, but our social one is. This is why the various projects for fact-checking claims in the news, while valuable, don’t convince people. Belonging is stronger than facts (emphasis mine)(Benkler et al).”

This is not a phenomenon exclusive to conservatives. Liberals and the left are truly astonishingly susceptible to right wing manipulation, and in fact could learn a thing or two from their strategies to combat them and combat anti-intellectual impulses in ourselves. Benkler et al. are not wrong that fact-checking in the news does not convince people. The stubborn affirmation of fact-checking and digital literacy in the curriculum as a near-panacea, even when there are concerns that the pedagogical philosophies underlying something like California ICT Digital Literacy curriculum, for example, can cause more harm than good if not approached with more nuance.

Don’t get me wrong — I believe that fact-checking apps such as NYT’s fact-checking app that established veracity and context in statements made in the 2016 Clinton-Trump presidential live debates in real time or websites like FactCheck.orgare net goods in the world. But that these have been taken as a near panacea in ways that, as we’ll go over in the next two entries, can misrepresent power in ways that have consequences for how we deal with polarization.

In the next installment of this series, I am going to look at how and why exposure to new points of view is not inherently a virtue, what scientists can learn from climate change deniers and antivaxxers, and suggest a potential episode script for another Bad Time in which everything in our world is exactly the same except the show Black Mirror is a satirical comedy because at least one of the “bubble bursting” initiatives listed above falls under the Can’t Make This Up category.

Works Cited:

Benkler, Yocai, Rob Faris, Hal Roberts, and Nikki Bourassa. “Understanding Media and Information Quality in an Age of Artificial Intelligence, Automation, Algorithms and Machine Learning.” The Berkman Klein Center at Harvard, July 12 2018. Accessed: July 2018.

Kaiser, Jonas and Adrian Rauchfleisch. “Unite the Right? How YouTube’s Recommendation Algorithm Connects The U.S. Far-Right.” Medium, D&S: Dispatches from the Field, April 11, 2018. Accessed: July 2018.

Pariser, Eli. The Filter Bubble: What the Internet is Hiding from You, Penguin Press, 2009.

2 comments